White people don't really like to talk about race, do we?

Some wax poetic about colorblindness and a "post-racial America," as if talking like that will make it so, but remaining oblivious to race is a luxury enjoyed only by those who've not been on the receiving end of racism.

"White folks are sometimes looking for the slur; this is a pattern of institutional neglect," said @timjacobwise. #TrayvonMartin #nerdland

— Melissa @ MSNBC (@MHPshow) March 25, 2012

White people get to laugh at their mistakes. Dust themselves off and move on. Black kids don't get those chances. But y'all knew that.

— Kimberly N. Foster (@KimberlyNFoster) March 26, 2012

There's a section of the White community that hates when race is mentioned. Ever. To not HAVE to deal w/ race? That's called PRIVILEGE.

— Elon James White (@elonjames) March 26, 2012

White privilege is an invisible knapsack, conferring benefits to some that are denied to others. We take for granted many of the privileges we enjoy that are conferred by race and not merit.

Black people have been afraid of white people wearing hoods much longer than white people have feared black people wearing hoodies.

— David Walker (@badazzmofo) March 23, 2012

thnx @GeraldoRivera! i FORGOT what it was like to be a POC before you reminded me how to dress to avoid being murdered #TrayvonMartin

— Franchesca Ramsey (@chescaleigh) March 23, 2012

Black parents should teach their children not to wear hoodies. But white people don't need to have any such conversation.

— Basseyworld (@BasseyworldLive) March 23, 2012

Some white people do notice: we see injustice and inequality, and our hearts are heavy, but we still are reluctant to talk about race.

Our silence does not go unnoticed.

sigh. still observing silence about #TrayvonMartin from a lot "progressive Christian social justice-oriented" bloggers.

— laura(@lolaelizabeth) March 22, 2012

progressive Christians who write post after post calling for lawmakers and churches to fight poverty, climate change, and other injustices

— laura(@lolaelizabeth) March 22, 2012

but cases of blatant racial bias? *crickets*

— laura(@lolaelizabeth) March 22, 2012

Also struck by Xians who talk about internat'l justice to show the love of Jesus etc and ignore black Xians RIGHT HERE.

— Grace (@graceishuman) March 23, 2012

So, y'know, white Christians. Don't be surprised that there are so few people of color in your communities when you act like this.

— Grace (@graceishuman) March 23, 2012

Coming on the heels of the Invisible Children/KONY2012, a viral justice campaign which occupied a tremendous amount of conversation, especially among young white Christians, the lack of attention to Trayvon Martin's death was especially glaring.

{Several white bloggers did offer comments this week: Jen Hatmaker, Momastery, Kristen with "required reading", and Natalie with this piece on race and faith.}

I don't know how we choose what to speak out about--or not. For many, racial injustice is off our radar, especially if we only interact with white people. Perhaps we prefer to keep hard stories at arms' length.

I used to want to simply turn away from the news because "it was so depressing." And it IS depressing, but ignorance ain't an option.

— Saeed Jones (@theferocity) March 25, 2012

Instead of turning away from depressing news, I keep watching, but also surround myself with solution-oriented/loving people.

— Saeed Jones (@theferocity) March 25, 2012

"If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor." ~ Archbishop Desmond Tutu

— Whitney (@arieswym) March 25, 2012

Sometimes, we are afraid. We don't know what to say or how to say it, and don't want to step on toes. We fear doing it wrong, so we don't say anything.

how to express solidarity across lines of privilege can be tough. it has to be determined by ppl being supported.

— Grace (@graceishuman) March 25, 2012

Talking about race is not easy. Relinquishing privilege won't be, either.

We will get it wrong. We may look foolish or ignorant, and it will certainly be uncomfortable--a small price to pay compared to the racial injustice suffered historically and presently in this country.

Learning is a process. But we don't need to be experts or have answers in order to listen, reflect, demonstrate compassion, or amplify the voices of people of color.

It's a start.

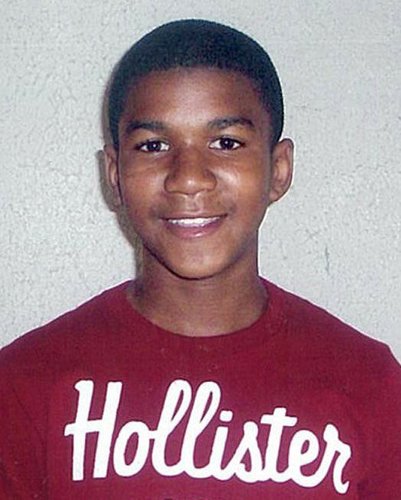

Trayvon Martin was murdered one month ago to this day. And on the anniversary of this tragedy, the media has converted him into a criminal.

— LEFT (@LeftSentThis) March 26, 2012

Tweet